Article:

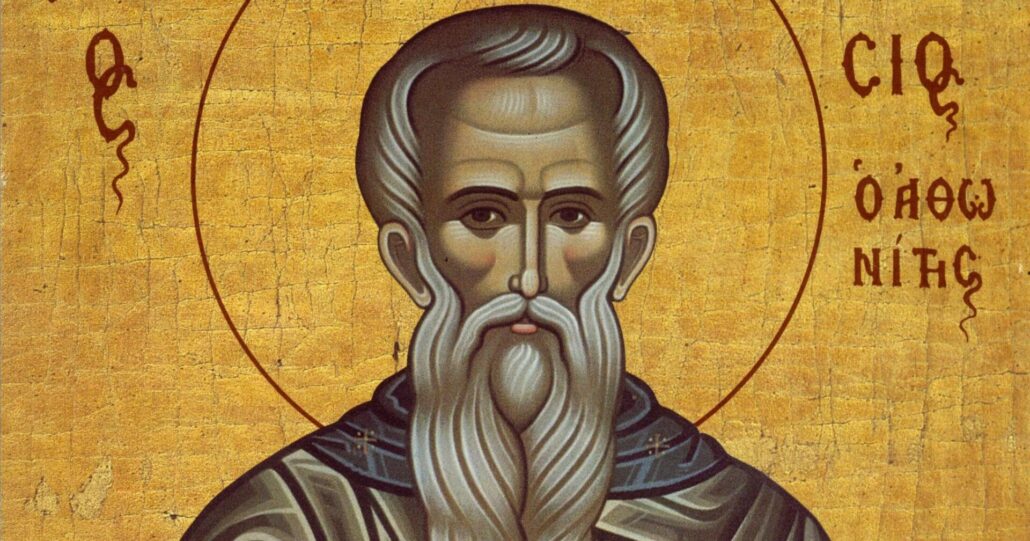

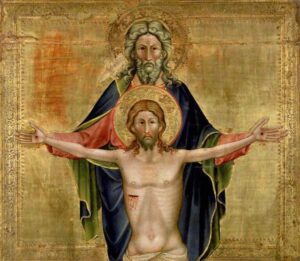

The Young Champion of Nicaea. He was 30 years old at the time of the Council of Nicaea and only a deacon, yet he was one of the great paladins of the faith. And his struggle did not begin during the Council; even before, when he was even younger, he had identified the error and its grave consequences and had begun to dismantle it. Athanasius was born in Egypt around 295 AD, probably in Alexandria. There is only conjecture about his family, but it is clear that he received an excellent education, as evidenced by his writings and the depth of his thought. In his youth, he associated with the patriarch of the anchorites, Saint Anthony, of whom he would become the great biographer, either because he lived for some time as his disciple in the desert or, what seems more founded, because he spent periods of time with him.

When the Arian controversy erupted between 318-320 AD, he was one of the two deacons whose signatures appear on the encyclical letter that Bishop Saint Alexander sent to his colleagues. And, as we know, he was the secretary whom the elderly Alexander took to the Council of Nicaea, where he earned widespread admiration, as Saint Cyril of Alexandria later recounted in a letter to the monks of Egypt. But at Nicaea, his mission was only beginning, and he would still have to suffer greatly in defense of the Catholic creed.

Saint Alexander died in May 328 AD. Less than two months later, the young Athanasius, then no more than 33 years old, was ordained as bishop and successor. It is said he was designated by the dying Alexander himself, and the people acclaimed this decision, and he was confirmed by the orthodox bishops despite opposition from the schismatic (Meletian) and heretical (Arian) parties. Of course, these parties spared no means to complicate the election, including slanderous campaigns, of which they were specialists.

Through many vicissitudes, Athanasius governed his extensive ecclesiastical territory for almost half a century and suffered at least five exiles because of his faith. He had a tremendous sense of humor that could be biting in some cases, and was always spontaneous. His fortitude was unshakable, especially during the difficult times he endured when he was persecuted and banished. He had a singular passion for the purity of Catholic dogma and olfaction for error and heresy that very few other prelates in the history of the Church have possessed. He began his theological work when he was barely old enough to shave, as he was a young man of 23—scarcely a deacon—when he wrote his works Against the Gentiles and On the Incarnation, which Saint Jerome seems to consider as two parts of a single treatise. It is understandable, then, that when the Arian problem arose, the spirited deacon had much to do with the doctrinal condemnations that emanated from the pen of Bishop Alexander.

The doctrine of Arius was full of subtleties and transpositions between philosophy and faith. Saint John Henry Newman, in his work The Arians of the Fourth Century, considered it a matter of Jewish prejudices rationalized through a mixture of poorly digested Aristotelian ideas, to which others add Platonic principles and methods as well. Athanasius penetrated deeply and quickly to the essence of the errors and refuted them with lucidity and tenacity. As we said in previous entries, some attribute to him the recourse to the key term of the Council of Nicaea, the homoousion, “consubstantial,” although there are many arguments to think the idea came from the other great champion of Nicaea, Hosius of Córdoba.

Although the Nicene Creed made things clear regarding the faith, intrigues and ecclesiastical-court machinations would not cease for decades and even centuries. Eusebius of Nicomedia, who took up the philo-Arian or directly Arian cause, ended up influencing Constantine again and wresting from him dispositions that compromised what had been defined at Nicaea. Athanasius opposed this resolutely, maintaining that there could be no communion between the Church and those who denied the divinity of Christ. A rain of slanders began to fall upon him, for slander is the devil’s favorite weapon, as Rossini so wonderfully made Don Basilio sing in the very famous aria from The Barber of Seville…

…it’s a little wind,

a very gentle breeze,

which, imperceptible, subtle,

lightly, softly,

begins to whisper.

[And] in a low, hissing voice,

it runs about, it runs about,

it goes buzzing, it goes buzzing;

into people’s ears

it skillfully introduces itself

and heads and brains…

it stuns and swells (…)

In the end, it overflows and bursts,

it spreads, it redoubles

and produces an explosion,

like a cannon shot! (…)

And the unhappy slandered one,

vilified, crushed

under the public lash,

may consider himself lucky

if he dies.

I believe we are all willing to subscribe to this, we who were born in this era where defamation and slander are our daily bread. Annoying, of course.

Well, the Don Basilio of the 3rd century, who was the Bishop of Nicomedia, Eusebius the troublemaker, managed to convene a rigged synod capable of condemning the very champion of the faith, who had to escape by boat. The episode ended with his first exile in Trier, today Germany, which lasted two and a half years.

We will not recount the life of Athanasius here; if anyone wants to read an adventure book that carries their imagination from the sands of the Egyptian desert to the forests of misty Germany, crossing the Mediterranean again and again, they need only get a good hagiography of this saint. His journeys from his see into exile—Rome, Germany, the caves of the anchorites in the wilderness—followed one after another for a total of five. And they lasted for years! His persecutors were always the partisans of that ambiguous, cunning, sly Eusebius, who climbed the ecclesiastical hierarchy until he nestled himself beside the throne of Constantine and some of his successors. Those of his party—for he ended up having henchmen and epigones—proved his equals and continued to disturb the life and governance of the greatest bishop of the 4th century.

Pope Julius was unconditionally supportive of Athanasius; Liberius first supported him but, weak in character and himself punished with exile, ended up signing some ambiguous and compromising formula which served to again give the Arian party a great advantage.

But the exiles of Athanasius were in God’s plans, like all things, down to the fall of the last of our hairs. And the Lord of History used them so that the great champion of the faith might carry and firmly fasten the faith of Nicaea to the ends of the then-known world, and not only dogmatic orthodoxy but also the spiritual monastic ideals of Anthony and his monks, whose life he wrote about, preached, and disseminated, helping to pave the way for monasticism in the very heart of Europe. For the devil stirs the pot, but he never manages to put the lid on it. That is exclusive to God.

Furthermore, the years of respite in exile, far from the arduous toil of governance—especially the six years spent in the desert of Upper Egypt among the monks—gave Athanasius time to compose some of his most magnificent works (Apology to Constantius, Apology for His Flight, Letter to the Monks, History of the Arians) which caused his enemies’ schemes to backfire; and this despite gunpowder not having been invented yet.

The confessor of the faith died peacefully in his own bed, surrounded by his clergy and mourned by the faithful of Alexandria. The subsequent centuries have always called him a titan of the faith. In contrast, of those who tried to silence him and embitter his life, of those who bet on amphibologies and ambiguities to deflate the Christian faith and its demands, only a faint recollection remains, which they owe to the great Bishop of Alexandria; for of them, we only remember that they were “the nonentities who hated Athanasius.”

Fr. Miguel Angel Fuentes, IVE

Original Post: Here