Article:

Arius, Not Eternal, But Ever-Living. Arius was not the first heretic to appear on the horizon, but he certainly stirred up one of the worst dust storms. He even brought the Church to the brink of collapse (if it weren’t for the Holy Spirit!). The case of Pelagius and his moral heresy might be considered a step below. The figure we are discussing is believed to have been born in Libya between 250 and 256 AD, meaning he was around 70-75 years old at the time of the Council. At an age when one should be preparing to die well, fools dedicate themselves to stirring the devil’s cauldron. In fact, he only survived another decade, dying in 336.

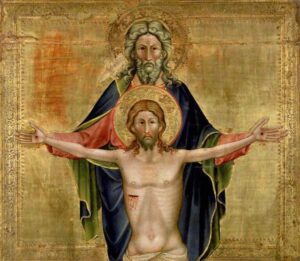

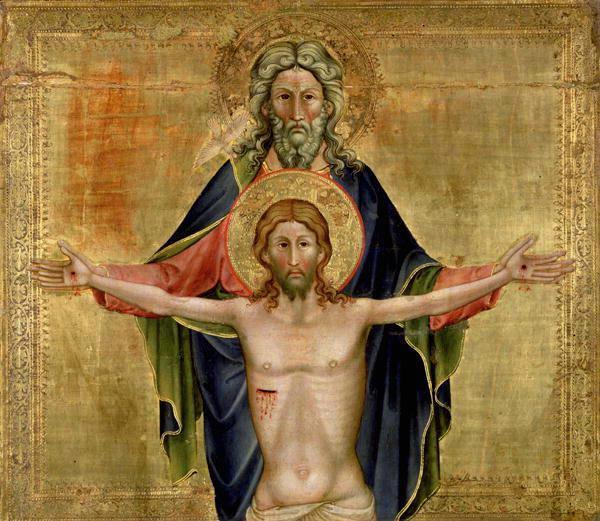

Arian theology was highly convoluted, inspired by Neoplatonic and Gnostic principles, and Arius was not its inventor ex ovo, as its main ideas have roots in the adoptionism of Paul of Samosata—who admitted only one person in God—and other early authors heavily influenced by still-unrefined philosophical ideas. José Antonio Sayés characterized Arian thought as rationalism and summarized its main assertion as follows: “It is not the Word who becomes man, but the man who, by divine grace, becomes divinized.” Stated thus, the thesis is very similar to that of some theologians of our time. Because what Arianism proposed applies to any man as a work of grace, but to explain Christ in this way is to make him a creature. And that is what Arius maintained, for whom Jesus Christ is not the incarnate Word—that is, a divine Person who assumes a human nature—but a creature that God creates as an intermediary between Himself and the creation of all other things.

Because for Arius, God cannot lower Himself to interact with creatures; not even to create them. He is absolutely (read: adulterously) transcendent to creation. Therefore, creation is mediated by the Word, who is God’s first creature. What the heretic could never explain—and the champions of the faith, like Athanasius, pointed this out to him—is why God can create the Word, if the problem is that He cannot create other things. Well, heretics don’t explain everything; they only pretend to explain. So let’s not ask Arius for coherence.

But what Arius did achieve was to offer worldly rationalism a Christ seemingly more comprehensible to its mind. Because every attempt to shrink the mystery is nothing more than that: a reduction to see if we can make it fit into the poor ideas of our heads. And his explanation, utterly unclear and deliberately convoluted so that no one understood whether he said what he said, or seemed to say not what he said, or didn’t say what he seemed to say… gained enormous diffusion, finding adherents among many bishops who were already tainted by other errors like adoptionism and modalism, all of which are forms of Gnosticism.

But he also ran into champions of the faith, among whom were great bishops; even some individuals who, at the height of the fray, were mere youngsters, like the deacon Athanasius of Alexandria, who would become the primary hammer of this heresy, and who, at the time of the Council, was only 30 years old.

In summary, Arianism, with its many twists and subtleties, held that Jesus Christ is a creature. An exceptional creature, perfectly united to God, a universal medium of creation and salvation… but always a creature. And it gained adherents. Some fully embraced his doctrine; others not so much, but did not dare to stake themselves on orthodox doctrine. These are the ones we know as philo-Arians, some of whom swung like the best of pendulums from one side to the other.

The Council of Nicaea condemned the error of the Libyan, but did not manage to eradicate it. Athanasius, once made bishop of Alexandria, would still have to suffer five exiles because of it, for after Constantine, who endorsed the Nicene council, his sons were not up to the task and some of them heavily favored the heresy. Constantine himself surrounded himself in life with bishops who were, at the very least, philo-Arians, like the two Eusebiuses, one of Nicomedia and one of Caesarea.A little later, St. Jerome would encapsulate the drama of those times in a famous phrase: “ingemuit totus orbis et arianum se esse miratus est“; the whole world groaned to discover it had become Arian. At Nicaea, the faith was saved, but Arianism infected a part of the Catholic world, and its miasmas would spread for centuries. It penetrated the imperial army, and through it, spilled over into pagan peoples and frontier areas where the troops were stationed. Many of the barbarians who would later invade the Empire were not pagans but Arians, and that is the reason they so fiercely persecuted Christians faithful to the Nicene faith. In Spain, it was necessary to wait for Reccared I, king of the Visigoths, to profess the Catholic faith; and this would not happen until 587 AD, at the Third Council of Toledo.

Every so often, Arianism raises its head, led by some theologians. Today it is active again, if we consider what Cardinal Koch, Prefect of the Dicastery for Promoting Christian Unity, suggested not long ago, who expressly pointed out that “in our own Church the spirit of Arius has become very present again and a strong awakening of Arian tendencies is observed” (CNA Deutsch Nachrichtenredaktion, 20-12-2024). And, as he adds next, “already in the 1990s, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger recognized the true challenge facing Christianity today in a ‘new Arianism’ or, more softly, at least in a ‘quite pronounced new Nestorianism’.” Fr. Iraburu, in a chapter of his booklet Gracia y libertad, speaking of “current Arianism,” pointed out that it no longer appeals to the semi-Platonic speculative explanations of Arius, although his epigones walk the same path: Christ is man, not God. Whether they affirm that the person of Christ does not exist from all eternity, equal to the Father and the Holy Spirit, or whether they maintain that Jesus can be called God only in a certain way, i.e., insofar as He reveals Him in fullness. And he listed among the neo-Arians Edward Schillebeeckx, O.P., Anthony De Mello, S.J., Roger Haight, S.J., Jon Sobrino, S.J. The list could be truly extensive if we insisted.

In 1972, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith published Mysterium Filii Dei, a Declaration in which it denounced many erroneous assertions that reissued the Arian errors. There it said: “Clearly opposed to this faith are the opinions according to which it would not have been revealed and manifested to us that the Son of God subsists from eternity in the mystery of God, distinct from the Father and the Holy Spirit; and likewise, the opinions according to which the notion of the one person of Jesus Christ, born before all ages from the Father according to the divine nature, and in time from the Virgin Mary according to the human nature, should be abandoned; and, finally, the assertion according to which the humanity of Jesus Christ would exist, not as assumed into the eternal person of the Son of God, but rather in itself as a human person, and, consequently, the mystery of Jesus Christ would consist in the fact that God, in revealing Himself, would be present in the highest degree in the human person of Jesus.” These are new variants of Arianism. Fifty years after this declaration, the situation has not changed for the better—despite a great respite in the interim. If anything, perhaps it should be said that it has worsened and that the Arians of this 21st century continue to propose the same errors clothed in the fashion of our digital age. It is “millennial” Arianism.

But every Sunday we recite the Nicene Creed with fervor, and our acidity dissipates.