Question:

I would like to know if it is possible that a person who commits a disorderly act without being guided by any motive of contempt, hatred, defiance, or rebellion towards God, still commits an act against God. I do not understand why the morality of acts should be determined by something that is outside their intention.

Response:

There are people who think that it is not fair to classify an act as an offense to God that is done without intending to offend God. Many sins – it is said – are committed out of weakness, following a passion, and without seeking to offend God directly. In fact, many times one does not even think of God at the time of the act.

Some moralists – taking up this idea – have proposed a distinction, according to which, these acts could be classified in some cases as grave, but not as mortal, that is, they would not kill the spiritual life (the life of grace) in our souls.

I believe that the following statements should be made in this regard:

1) The act which in itself is a grave disorder against nature is also a grave offense against God and is sufficient to separate man from God.

St. Thomas, following St. Augustine, distinguishes in every sin a double dimension:

- On the one hand, it is constituted by a disordered inclination towards a creature; it is thus “conversio ad creaturam” (conversion towards the creature).

- On the other hand, it implies a separation from God, the ultimate goal of man; it is thus ‘aversio a Deo‘ (aversion to God).

It is true that it is possible to consider abstractly both aspects separately; but it is not possible to think, from this, that they can occur separately in reality. They are two faces of the same reality: “the same sin is in reality aversion and conversion, differing according to the relation to the different terms”.

Aversion with respect to the ultimate end is implied in the disordered tendency toward the finite end.

This is what Pope John Paul II expresses in the Exhortation Reconciliatio et paenitencia:

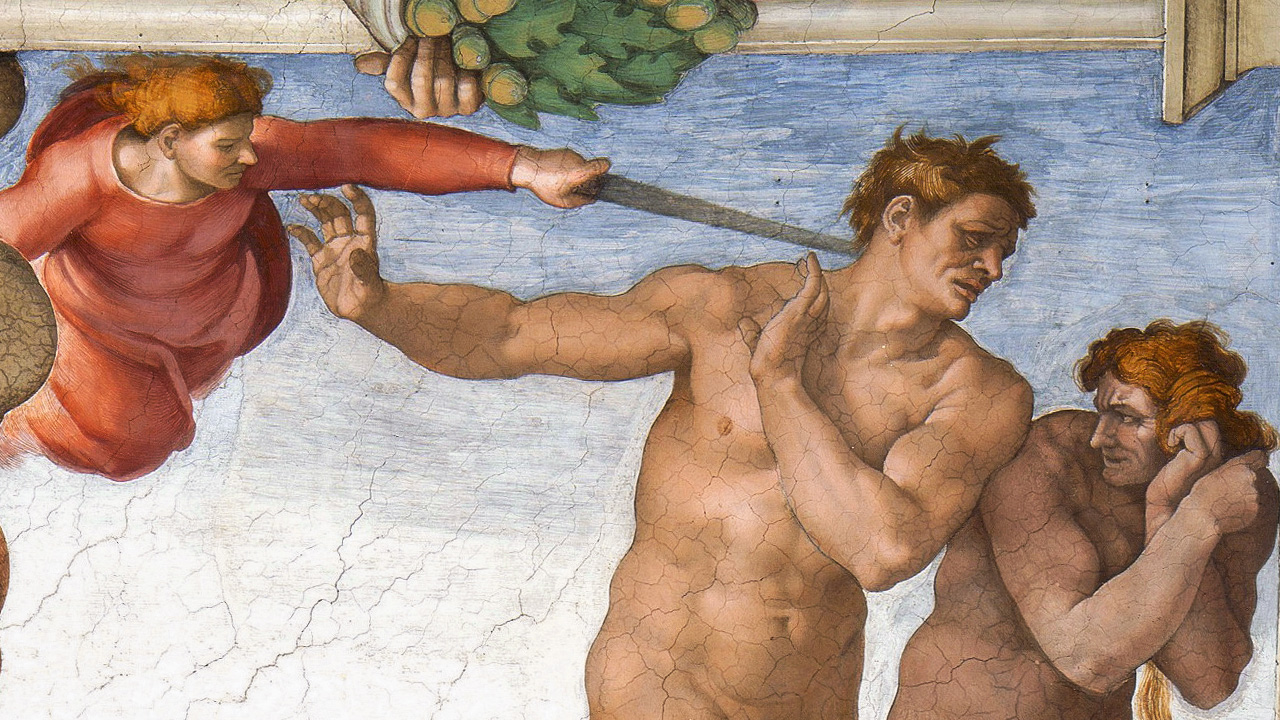

For man also knows, through painful experience, that by a conscious and free act of his will he can change course and go in a direction opposed to God’s will, separating himself from God (aversio a Deo), rejecting loving communion with him, detaching himself from the life principle which God is and consequently choosing death.

With the whole tradition of the church, we call mortal sin the act by which man freely and consciously rejects God, his law, the covenant of love that God offers, preferring to turn in on himself or to some created and finite reality, something contrary to the divine will (conversio ad creaturam). This can occur in a direct and formal way in the sins of idolatry, apostasy and atheism; or in an equivalent way as in every act of disobedience to God’s commandments in a grave matter. Man perceives that this disobedience to God destroys the bond that unites him with his life principle: It is a mortal sin, that is, an act which gravely offends God and ends in turning against man himself with a dark and powerful force of destruction.

And in the Encyclical Veritatis Splendor:

In point of fact, man does not suffer perdition only by being unfaithful to that fundamental option whereby he has made “a free self-commitment to God” (Dei Verbum, 5) With every freely committed mortal sin, he offends God as the giver of the law and as a result becomes guilty with regard to the entire law (cf. Jas 2:8-11)…

2) Notwithstanding what has been said, an abstract consideration of sin can be made from the philosophical point of view, with a certain independence of its theological aspect.

One can reflect on the purely natural dimension of sin. St. Thomas affirms: “The theologian considers sin chiefly as an offense against God; and the moral philosopher, as something contrary to reason.”

Such a view would consider sin in a particular way in its aspect of violation or opposition to the dictates of right reason. This does not prevent such a consideration from being necessarily incomplete.

3) It is subjectively impossible to perform an action that formally transgresses the order of reason without at the same time offending God, even if at that moment one neither thinks of God nor intends to offend him.

By an action that formally transgresses the order of reason I mean any act that is conscious of violating a rational norm. Let us distinguish in this respect:

a) In him who recognizes the existence of God and the elevation of man to the supernatural order by the work of grace, it is impossible for him to pretend to transgress the natural order without offending God, as author of the supernatural order, since God is author and legislator of both orders, and for the creature the ‘order of grace’ is the order of nature healed, perfected and elevated by grace, not an independent order. By sinning against the law of his reason he opposes the order which grace presupposes and elevates.

b) He who is unaware of the existence of the supernatural order because he never received nor was faith sufficiently proposed to him, by acting against the order of reason, offends God who is the author and legislator of the natural order.

Therefore, no one can formally sin against right reason without offending God, since the awareness he has of transgressing the rational order comes to him because he discerns the absolute obligation to perform the good contained in a given action or to avoid the evil identified in another. And this warning of an absolute obligation (which is imposed on our internal acts and not only on the actions that manifest themselves to the exterior), is a warning of something that is superior to ourselves (and therefore not dispensable), it is the perception of a transcendent, legislating Will, which is the Will of God. This is why Cardinal Newman affirmed that God Himself reveals Himself to us in the moral obligation to which we find ourselves subject.

For this reason, Pope Alexander VII condemned, with a decree of the Holy Office, on August 24, 1690, the conception that held the possibility of a sin that only violated the rational order without implying a transgression of the divine law. Concretely, he condemned the statement that said:

“Philosophic or moral sin is a human act not in conformity with rational nature and right reason; but theological and mortal sin is a free transgression of the divine law. A philosophic sin, however grave, in a man who either is ignorant of God or does not think about God during the act, is a grave sin, but is not an offense against God, neither a mortal sin dissolving the friendship of God, nor one worthy of eternal punishment.”

Fr. Miguel A. Fuentes, IVE

Original Post: Here

Other Post: Forgetting sins in confession