Question: I would greatly appreciate it if you could help me with these questions:

– What is the purpose of placing relics in altars? What is their function?

– Since when has the Church placed relics in altars?

– Are relics indispensable for dedicating an altar? If the answer is ‘yes’, could it happen that there are no relics available to dedicate a new altar? What is done in those cases?

– Does the lack of relics make liturgical celebrations illicit or invalid?

– What exactly is understood by relics? Are they the mortal remains of Saints? Are their clothing and personal items sufficient, or must they be mortal remains?

Thank you very much for your response.

J.O.

Answer:

I respond to your question with an article that I consider interesting; it is written by a member of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Peru and I believe it addresses the doubts you have raised.

Sincerely,

Father Daniel Cima, IVE

Relics in Altars

Relics are remains (in Latin: reliquiae = remnants) of the body of saints or blesseds. In a broad sense, objects that the saints or blesseds used during their life, or objects that have touched relics, are also included.

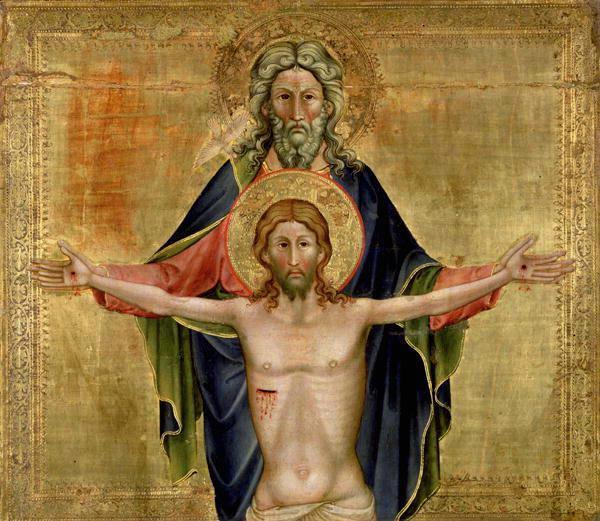

Doctrine

The teaching of the Council of Trent is fundamental: ‘Also the bodies of the holy martyrs and of the other saints who lived with Christ, who were living members of Christ and temples of the Holy Spirit, Consequently, those who think that veneration and honor are not due to the relics of the saints, or that these and other sacred monuments are uselessly honored by the faithful… are to be utterly condemned, as the Church has already long since condemned and now again condemns them.’ (Denzinger 985; cf. 998). Also related are the decisions concerning the veneration of sacred images from the Second Council of Nicaea (Dz 302) and chapter 62 of the Fourth Lateran Council concerning the abuse of relics.

The documents emphasize that Sacred Scripture presents cases where miracles were performed through relics (2 Kings 2:14; 13:21; Mt 9:20; Acts 5:15; 19:12; Rev 6:9). The very ancient practices of the Church are also mentioned (veneration of the tombs of Saint Peter and Saint Paul [Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History II, 25, Patres Graeci-Migne 20, 208s], Jerome [Against Vigilantius, Patres Latini-Migne 23, 361s] and the pious reservation of the relics of the martyrs).

The cult of relics is, as the Church always emphasizes, a relative cult, meaning the veneration shown to the relics is in relation to the person of the martyr and the saints, who are worthy of veneration in themselves (Dz 302, 337, 985). The ultimate reason (ultima ratio) for the cult of relics is always the ‘divine excellence that shines forth in all these diverse elements.’

The justification for the cult of relics stems from a simple human need to respect the person who has shown signs of holiness. This does not exclude the fact that the external forms of the cult of relics have varied greatly throughout times.

Liturgy

From the beginning, Christians have gathered on the anniversaries of the death of martyrs and saints to remember their luminous example and implore their intercession. During the persecution of Christians, they used to celebrate the Eucharist in the catacombs near or on the tombs of the martyrs and saints. These places were memorials, i.e., the place and circumstances of God’s special action in men. Recall, for example, the story of Origen’s father, who used to kiss the chest of his baptized son to venerate the presence of the Holy Spirit.

Later, altars and chapels and even basilicas were erected over or near the tombs of martyrs and saints, such as the Basilicas of Saint Peter and Saint Paul Outside the Walls in Rome. In the 5th century, we know that sometimes it was not possible to build the church exactly on the site, but in another more suitable location. They began to transfer the relics of the saint to this church and placed them in a crypt beneath the main altar.

It is nothing more than a logical consequence that other churches also wanted to have these signs of being united to the faith of the martyrs and saints. A custom developed of sharing with communities that did not have the tombs of saints by sending them some relics. These were enclosed in the stone or wood of the main altar.

Nowadays, the ritual provides that the altar is consecrated by the bishop. And in the place on the altar where the Eucharistic signs of the body and blood of Christ usually rest, a cavity is opened where the bishop deposits the relics, which are then covered with a smooth stone so that it forms a flat level with the table of the altar. This stone is fixed with mortar.

All consecrated churches have relics in the main altar.

To conclude, we wish to cite a passage from Saint Gregory of Nyssa who, after pondering the beauty of the temples erected in honor of the saints, writes: ‘The believer approaches the tomb with the firm conviction that touching it is already a sanctification and a blessing. If he is allowed to take away something of the dust accumulated at the resting place of the martyr, he considers it a great gift. And when it is permitted to touch the relics themselves, if this were ever possible for our happiness, only those who have experienced it know how much it is to be desired and how precious a reward it is for the one who prays.’ (PG 46, 740).

And for our Evangelical brothers who so recklessly apply the Old Testament prohibition of worshipping statues of false gods to the veneration of martyrs and saints – we could even speak of slander and false witness – we offer what Saint Jerome already wrote in the 4th century: ‘We do not worship [the relics], worried lest we bow down to the creature rather than to the Creator, but we venerate the relics of the martyrs in order to worship more and better Him of whom they are witnesses.’ (Ad Riparium, PL 22, 907).

Note: Martyr means ‘witness’

Fr. Daniel Cima, IVE

Original Post: Here